Fatdog64 800 development update

We have finally completed the base of the next generation Fatdog64 800. We have it running with 4.18.5 kernel (this will probably change nearer to release).We are still in the process of fine-tuning it, and trimming the size down. Size growth is unavoidable because newer version of the software are almost always bigger due to feature creep.

Apart from fine-tuning it, we're going to do the usual "eat own dog food" which is to run it ourselves for day-to-day use; this way we can iron out the most obvious bugs.

Once this get stable enough, it will then be ready for alpha release.

No comments - Edit - Delete

Some random updates

OK, let's start with Barry K, the original author of Puppy Linux and the spiritual grandfather of every "dog"-themed Linuxes out there, Fatdog included

For you who haven't read Barry K's blog recently, you should check it out. Barry has come out with new interesting stuff that should spice out your "Puppy" experience (strictly speaking, it's not Puppy Linux anymore - Barry handed over the baton long time ago. Instead Barry now does Quirky/EasyOS/etc - but as far as we're concerned, it's a "puppy" with a quote

).

).

Barry is also branching to 64-bit ARM (aarch64). I'm sure he will soon release an 64-bit ARM EasyOS. If you remember, Barry was also one of the first to venture to 32-bit ARM a while ago (a tad over 6 years ago) and made a Puppy that ran on the original Raspi. Quite an achievement considering that the original Raspi was barely able to run any desktop at all - but that is Puppy at its best, showing the world that even the weakest computer in the world can still run a desktop (as long as it's Puppy

). It was also one of the motivation that made me do FatdogArm.

). It was also one of the motivation that made me do FatdogArm.

Speaking about Raspi and FatdogArm, I have also recently pulled out my Raspi 3 out of retirement. But this time I'm not doing it for desktop replacement, but mainly because I'm interested to use it for what it was originally made: interfacing with stuff. Direct GPIO access, I2C and SPI is so interesting with the myriad of sensor packages out there. I've been playing with Arduino for a while and while it's cool, it's even cooler to do it using a more powerful platform. Now this article shows you how to do it directly from the comfort of your own PC (yes, your own desktop or laptop), if you're willing to shell out a couple of $$ to get that adapter. I did, and it is quite fun. Basically it brings back the memory of trying to interface stuff using the PC's parallel port (and that adapter indeed emulates a parallel port ... nice to see things haven't changed much in 30 years). But it's speed is limited to the emulation that it has to go through - the GPIO/I2C/SPI has to be emulated by the kernel driver, which is passed through USB bus, which then emulated by the CH341 on the module. If you want real speed, then you want real device connected to your system bus - and this is where Raspi shines. I haven't done much with it, but it's refreshing to pull out the old FatdogArm, download wiringPi and presto one compilation later you've got that LED to blink. Or just access /sys/class/gpio for that purpose.

Now on to Fatdog64 800. I'm sure you're dying to hear about this too

OK. As far as Fatdog64 800 is concerned - we've done close to 1,100 packages. We're about 200 packages away from the finish line. As usual, the last mile in the marathon is the hardest. It's bootloaders, Qt libs and apps, and libreoffice. Here's crossing your finger to smooth upgrading of all these packages.

OK. As far as Fatdog64 800 is concerned - we've done close to 1,100 packages. We're about 200 packages away from the finish line. As usual, the last mile in the marathon is the hardest. It's bootloaders, Qt libs and apps, and libreoffice. Here's crossing your finger to smooth upgrading of all these packages.

Speaking about updates, I've also decided to go for the newest bluetooth stack (bluez). I have been a hold-on on bluez 4 for the longest time, simply because the bluez 5 does not work with ALSA - you need to use PulseAudio for sound. But all of that have changed, ther e is now an app called bluez-alsa that does exactly that. I've been thinking to do it myself were it not there; but I've been thinking too long

Anyway, I'm glad that it's there. Bluez 5 does have a nicer API the last time I looked at it (as in, more consistent) though not necessarily clearer or easier to use than Bluez 4. But that's just Bluez.

Anyway, I'm glad that it's there. Bluez 5 does have a nicer API the last time I looked at it (as in, more consistent) though not necessarily clearer or easier to use than Bluez 4. But that's just Bluez.

Well that's it folks for now. And in case I don't see you... good afternoon, good evening, and good night

No comments - Edit - Delete

Github fallout and what we can learn from that

Hahaha. What would I say.It's the talk of the town: Microsoft buys Github.

Why are you surprised? It's long time coming. See my previous articles about FOSS. Add the fact that Github fails to make a profit. Their investors want out; they would welcome a buyer. **Any** buyer.

But today I don't want to talk about the sell-out; there are already too many others discussing it. Instead I'd like to ponder on the impact.

Rightly or wrongly, many projects have indicated that they will move away. These projects will not be in github anymore, either in near future or in immediate future. What's going to happen? Some of these projects are libraries, which are dependencies used by other projects.

People have treated github as if it is a public service (hint: it never has been). They assume that it will always exist; and always be what it is. Supported by the public APIs, people build things that depends on github presence; that uses github features. One notable "things" that people build are automated build systems, which can automatically pull dependencies from github. Then people build projects that depends on these automated build tools.

What happens to these projects, when the automated build tools fail because they can no longer find the dependencies on github (because the dependent project has now moved elsewhere)? They will fail to build, of course. And I wonder how many projects will fail in the near future because of this.

We've got a hint a couple years ago, here (which I also covered in a blog post, here). Have we learnt anything since then? I certainly hope so although it doesn't look like so.

It's not the end of the world. Eventually the author of the automated build tools will "update" their code libraries and will attempt to pull the dependencies from elsewhere. You probably need a newer of said build tools. But those github projects don't move at one step; they move at the convenience of the project authors/maintainers. So, you will probably need to constantly updates your automated build tools to keep track with the new location where the library can be pulled from (unless a central authority of sorts is consulted by these build tools to decide where to pull the libraries from - in this case one only needs to update said central authority). It will be an "inconvenience", but it will pass. The only question is how long this "inconvenience" will be.

How many will be affected? I don't know. There are so many automated build tools nowadays (it used to be only "make"). Some, which host local copies of the libraries on their own servers, won't be affected (e.g. maven). But some which directly pulls from github will definitely get it (e.g. gradle). Whatever it is, it's perhaps best to do what I said in my earlier blog post - make a local copy of any libraries which are important to you, folks!

Github isn't the only one. On a larger scale (than just code repositories and code libraries), there are many "public service" services today, which aren't really public service (they are run by for-profit entities). Many applications and tools depend on these; and they work great while it lasts. But people often forget that those who provide the services has other goals and/or constraints. People treat this public service as something that lasts forever, while in actuality these services can go down anytime. And every time the service goes down, it will bring down another house of cards.

So what to do?

It's common sense, really. If you really need to make your applications reliable, then you'd better make sure that whatever your application depends are not "here today gone tomorrow". If you depend on certain libraries make sure you have local copy. If you depend on certain services make sure that those services are available for as long your need it. If you cannot make sure of that, then you will have to run your own services to support your application, period. If you cannot run the services in house (too big/too complex/too expensive/etc), then make sure you external services you depend on is easily switchable (this means standards-based protocols/APIs with tools for easy exporting/importing). Among other things.

Hopefully this will avoid another gotcha when another "public service" goes down.

No comments - Edit - Delete

New Fatdog64 is in the works

It's the time of the year again. The time the bears wake up from hibernation. After being quiet for a few months, the gears start moving in the Fatdog64 development.Fatdog64 721 was released over 4 months ago. It was based on LFS 7.5, which was cutting edge back in 2014 (although some of the packages have younger ages as they got updated in every release).

As I have indicated earlier (in 720 beta release, here), 700 series is showing its age. Compared to previous series, the 700 series is actually the longest-running Fatdog series so far, bar none.

But everything that has a beginning also has an end. It's time to say goodbye to 700 series and launch a new series.

The new series will be based on LFS 8.2 (the most recent as of today). This gives us glibc 2.27 and gcc 7.3.0. Some packages are picked up from SVN version of BLFS, which is newer.

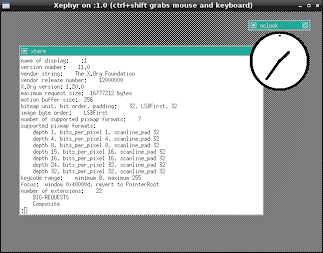

How far have we gotten with this new release? Well, as of yesterday, we've got Xorg 1.20.0 running with twm, xterm and oclock app running from its build sandbox.

Hardly inspiring yet, but if you know the challenge we faced to get there, it's a great milestone.

As it is usual with Fatdog64, however, it will be released when it is ready. So don't hold your breath yet. If 721 is working well for you, hang on to it (I do!). But at least you know that wouldn't be the last time you heard of this dog.

On a special note, I'd like to say special thanks to "step" and "Jake", the newest members of Fatdog64 team (and thus is still full of energy - unlike us the old timers hehe). While I have been shamelessly away from the forum for many reasons, "step" and "SFR" continue to support Fatdog64 users in the forum. My heartful thanks to both of them.

Of course, also thanks to the wonderful Fatdog64 users who continue to support each other.

1 Comment - Edit - Delete

Measure LED forward voltage using Arduino

Arduino is used for many things, including testing and measuring component values.Somebody has made a resistance meter:

http://learningaboutelectronics.com/Articles/Arduino-ohmmeter.php

Another has made a capacitance meter:

https://www.arduino.cc/en/Tutorial/CapacitanceMeter

Yet another has made an inductance meter:

https://foc-electronics.com/index.php/2017/12/06/how-to-measure-inductance-with-an-arduino/

There is one missing: determine LED forward voltage.

LED comes in variety of colours, and these variations comes from different materials and different doping densities. As a result, the forward voltage of these LEDs are also not the same - lower-energy-light LEDs (e.g. red) usually require less forward voltage than higher-energy-light LEDs (white or blue). The only sure way to know is by reading its datasheet.

But what if you don't have the datasheet? Or you don't know what is the datasheet for some particular LEDs? (e.g. LEDs you salvage from some old boards).

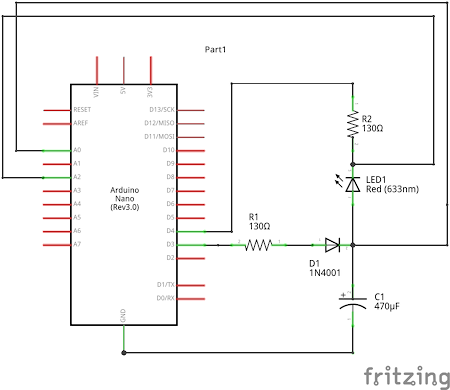

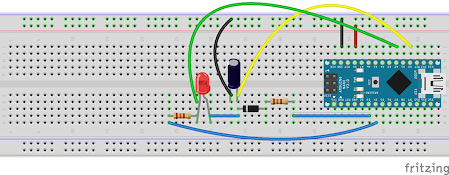

The following Arduino circuit should help you. It helps you to figure out what is the forward voltage for an LED.

Connections

Sketch

Get the sketch.

Principle of operation

Initially we have both D3 and D4 as high (=5V). This charges the capacitor, and turns off the LED.

Then drop both D3 and D4 to low. The diode prevents the capacitor from bleeding off its charge through D3, so the only way it can discharge now is via the LED.

A0 measures the capacitor voltage.

A2 measures series resistor voltage.

A2-A0 gives you the LED voltage.

In the ideal situation, you expect to see that A0 and A2 will keep dropping off until the conduction suddenly stops, A2 becomes zero (because no more current flows through it), and then A0 will give you the LED forward voltage.

Of course, in real world this does not happen. If you test that circuit you will find that the LED will keep giving out light even when it's below its official forward voltage, and if you wait until the current is zero, the A0 voltage you get will be very much below the nominal forward voltage.

So how do we know how to stop measuring? Well, most LEDs are usually specified to be "conducting" when it pass at least 5mA of current. So when we detect the current across the resistor to be less than 5mA, we stop measuring and declare that the A2-A0 of the last measurement as the forward voltage.

Oh, how do you get the LED current? LED current is the same current that pass through its series resistor (ignoring current going out to A2). The current in the series resistor is simply its voltage (A2) divided by its resistance (130R).

Caveat

The voltage-current relation of a LED is the same as any diode - it's exponential. In other words, the forward voltage depends on the amount of current that flows (or better yet: the current that flows depend on the applied voltage). There is no single one fixed "forward voltage"; the LED will actually conduct and shine (with varying brightness) on voltages lower or higher than the official forward-voltage.

Ok, that helps. But how about forward current?

Typical LEDs uses 20mA forward current. This is regardless of the colour or the forward voltage. So there you have it. Of course, main exception for this rule is super-bright high-wattage LEDs which is meant for room illumination or for torches. These can easily pass 100mA, and some can even crank up to 500mA or more. Forward voltages on these kind of LEDs can vary a lot depending on whether you're passing 5mA or 500mA. The tester above won't work properly with these kind of LEDs.

FAQs

Q1: Why pin D3 and D4? Not D8 or D9?

A1: Because I like it that way. You can change it, but be sure to change the code too.

Q2: Why analog pins A0 and A2?

A2: Because I like it that way too. Actually, that's because an earlier design used 3 analog pins, but later on I found out that one of them (located in A1) isn't necessary, but I've already wired the circuit with A2, so it stays there. Of course you can change it, but remember to update the code too.

Q3: Why do you use 130R?

A3: 130R is the series resistor you use for LEDs with 2.4 forward voltage (green LEDs usually), which is somewhat in the middle of the range for LED forward voltages. Plus, they're what I have laying around.

Q4: Why 470uF?

A4: That's what I have laying around too. You can use other values, but make sure they're not too small.

Q5: The diode - IN4001 - you also use that because that's what you have laying around?

A5: Actually you can use any diode. In my circuit I actually used IN4007 because that's what I have laying around :)

And finally:

Q6: Why do you have separate D3 and D4? Since they will be brought HIGH and LOW at the same time, why not just use one pin?

A6: Yes, you can do it that way (remember to change the code). But using two pins make it clearer of what is happening.

No comments - Edit - Delete

Spectre on Javascript?

The chaos caused by Spectre and Meltdown seems to have quieten down. Not because the danger period is over, but well, there are other news to report. As far as I know the long tail of the fix is still on-going, and nothing short of hardware revision can really fix them without the obligatory reduction in performance.Anyway.

One of the those who quickly released a fix, was web browser vendors. And the fix was to "reduce granularity of performance timers" (in Javascript), because with high-precision timers, it is possible to do Spectre-like timing attack.

This, I don't understand. How could one perform Spectre or even Spectre-like timing attack using Javascript? Doesn't a Javascript program run in a VM? How would it be able to access its host memory by linear address, let alone by physical address? I have checked wasm too - while it does have pointers, a wasm program is basically an isolated program that lives in its own virtual memory space, no?

In other words - the fix is probably harmless, but could one actually perform Spectre or Spectre-like attack using browser-based Javascript in the first place?

That is still a great mystery to me. May be one day I will be enlightened.

No comments - Edit - Delete

Spectre and Meltdown

Forget about the old blog posts for now.Today the hot item is Spectre and Meltdown. It's a class of vulnerabilities caused by CPU bugs that allows an adversary to steal sensitive data, even without any software bugs. Nice.

Everyone and his dog is talking about it, offering their opinions and such. Thusly, I feel compelled to offer my own.

Mind you, I'm not a CPU engineer, so don't take this as infallible. In fact, I may be totally wrong about it. So treat it like how you treat any other opinions - verify and cross-check with other sources. That being said, I've done some research about it myself, so I expect that I'm not too much fooled by myself :)

Overview

There are 3 kinds of vulnerabilities: Spectre 1, Spectre 2, and Meltdown.

In very simplified terms, this is how they work:

1. Spectre 1 - using speculative execution, leak sensitive data via cache timing.

2. Spectre 2 - by poisoning branch prediction cache, makes #1 more likely to happen.

3. Meltdown - Application of Spectre 1: read kernel-mode memory from non-privileged programs.

How they work

So how exactly do they work? https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com.au/2018/01/reading-privileged-memory-with-side.html gives you the super details of how they work, but in the nutshell, here it is:

Spectre 1 - Speculative execution is a phantom CPU operation that supposedly does not leave any trace. And if you view it from CPU point of view, it really doesn't leave any trace.

Unfortunately, that's not the case when you view it from outside the CPU. From outside, a speculative execution looks just like normal execution - peripherals can't differentiate between them; and any side effects will stay. This is well known, and CPU designers are very careful not to perform speculative executions when dealing with external world.

However, there is one peripheral that sits between CPU and external world - the RAM cache. There are multiple levels of RAM cache (L1, L2, L3), some these belongs to the CPU (as in, located in the same physical chip), some are external to the CPU. In most designs, however, the physical location doesn't matter: wherever they are, these caches aren't usually aware of differences between speculative and normal execution. And this is where the trouble is: because the RAM cache is unable to differentiate between these two, any execution (normal or speculative) will leave an imprint in the RAM cache - certain data may be loaded or removed from the cache.

Although one cannot read the contents of RAM cache directly (that would be too easy!), one can still infer information by checking whether certain set of data in inside the RAM cache or not - by timing them (if it's in the cache, data is returned fast, otherwise it's slow).

And that's how Spectre 1 works - by doing tricks to control speculative execution, one can perform an operation which normally isn't allowed to leave RAM cache imprint, which can then be checked to gain some information.

Spectre 2 - Just like memory cache and speculative execution, branch prediction is a performance-improvement technique used by CPU designers. Most branches will trigger speculative execution; branch prediction (when the prediction is correct) makes that speculation run as short as possible.

In addition, certain memory-based branch ("indirect branch") uses small, in-CPU cache to hold the location of the previous few jumps; these are the locations from which speculative execution will be started.

Now, if you can fill this branch prediction cache with bad values (="poisoning" them), you can make CPU to perform speculative execution at the wrong location. Also, by making the branch prediction errs most of the time, you make that speculative execution longer-lived than that it should be. Together, they make it more easier to launch Spectre 1 attack.

Meltdown - is an application of Spectre 1 to attempt to read data from privileged and protected kernel memory, by non-privileged program. Normally this kind of operation will not even be attempted by the CPU, but when running speculative execution, some CPU "forget" to check for privilege separation and just blindly do it what it is asked to do.

Impact

Anything that allows non-privileged programs to read and leak infomation from protected memory is bad.

Mitigation Ideas

Addressing these vulnerabilities - especially Spectre - is hard because the cause of the problem is not a single architecture or CPU bugs or anyhing like it - it is tied to the concept itself.

Speculative execution, memory cache, and branch prediction are all related. They are time-proven performance-enhancing techniques that have been employed for decades (in consumer microprocessor world, Intel was first with their Pentium CPU back in 1993 - that's 25 years ago as of this time of writing.

Spectre 1 can be stopped entirely, if speculative execution does not impact the cache (or if the actions to the cache can be un-done once speculative execution is completed). But that is a very expensive operation in terms of performance. By doing that, you more or less lose the speed gain you get from speculative execution - which means, may as well don't bother to do speculative execution in the first place.

Spectre 2 can be stopped entirely if you can enlarge the branch prediction cache so poisoning won't work. But there is a physical limit on how large the branch cache can be, before it slows down and lose its purpose as a cache.

Alternatively, it can be stopped again in its entirety, if you disable speculative execution during branching. But that's what a branch prediction is for, so if you do that, may as well drop the branch prediction too.

Meltdown however, is easier to work out. We just need to ensure that speculative execution honours the memory protection too, just like normal execution. Alternatively, we make the kernel memory totally inaccessible from non-privileged programs (not by access control, but by mapping it out altogether).

Mitigation In Practice

Spectre 1 - There is no fix available, yet (no wonder, this is the most difficult one).

There are clues that some special memory barrier instructions (i.e. LFENCE) can be modified (perhaps by microcode update?) to stop speculative execution or at least remove the RAM cache imprint by undo-ing cache loading during speculative execution, on-demand (that is, when that LFENCE instruction is executed).

However, even when it is implemented (it isn't yet at the moment), this is a piecemail fix at best. It requires patches to be applied to compilers, or more importantly any programs capable of generating code or running interpreted code from untrusted source. It does not stop the attack fully, but only makes it more difficult to carry it out.

Spectre 2 - Things is a bit rosier in this department. The fix is basically to disable speculative execution during branching. This can be done in two ways. In software, it can be used by using a technique called "retpoline" (you can google that) - which basically let speculative execution chases its own tails (=thus effectively disabling it). In hardware, this can be done by the CPU exposing controls (via microcode update) to temporarily disable speculative execution during branching; and then the software making use of that control.

Retpoline is available today. The microcode update is presumably available today for certain CPUs, and the Linux kernel patches that make use of that branch controls are also available today. However, none of them have been merged into mainline yet. (Certain vendor-specific kernel builds already have these fixes, though).

Remember, the point of Spectre 2 is to make it easier to carry out Spectre 1, so by fixing Spectre 2 it makes Spectre 1 less likely to happen to the point of making it irrelevant (hopefully).

Meltdown - This is where the good news finally is. The fix can be done, again, via CPU microcode update, or by software. Because it may take a while for that microcode update to happen (or not all), the kernel developers have come up with a software fix called KPTI - Kernel Page Table Isolation. With this fix, kernel memory is completely hidden from non-privileged programs (that's what "isolation" stands for). This works, but with a very high-cost in performance: it is reported to be 5% at minimum, and may go to 30% or more.

Affected CPUs

Everyone has a different view on this, but here is my take about it.

Spectre 1 - All out-of-order superscalar CPUs (no matter what architecture or vendor or make) from Pentium Pro era (ca 1995) onwards are susceptible.

Spectre 2 - All CPU with branch prediction that use cache (aka "dynamic branch prediction") are affected. The exact techniques to carry out Spectre 2 attack may be different from one architecture to another, but the attack concept is applicable to all CPUs of this class.

Meltdown - certain CPU get it right and honour memory protection even during specutlative execution. These CPUs don't need the above KPTI patches and they are not affected by Meltdown. Some says that CPUs from AMD are not affected by this; but with so many models involved it's difficult to be sure.

So that's it. It does not sound very uplifting, but at least you get a picture of what you're going to have for the rest of 2018. And the year has just started ...

EDIT: If you don't understand some of the terms used in this article, you may want to check this excellent article by Eben Upton.

No comments - Edit - Delete

Old blog posts

Long before time began, I had a blog. It was on a shared blogospace. I have long forgotten about it, but a few days ago I remembered about it and visited the site. To my surprise, it still exists; my old posts are still there. As if time stands still.I tried to login to that site, but Google wouldn't let me. I used Yahoo email for the login id; and I haven't accessed that email account for ages. When I tried to do that, it wouldn't recognise my password. In the light of Yahoo's massive data breach a couple years ago, this isn't surprising. I tried to recover the account using my other emails, but it didn't work either. Well, that's too bad, but I wouldn't have expected an abandoned blog to exist at all.

What I am going to do, instead, is I will scrape the text off that blog; and I will re-post some of the more interesting ones here. There are some unfinished posts there too; those whose subject I still remember I will publish the complete version here too.

No comments - Edit - Delete

Fatdog64 721 is Released

In the light of recent Spectre and Meltdown fiasco; the Linux kernel team has released patches to sort of workaround the problem.It's not free, you will get a performance hits anywhere from 5% to 30% depending on the kind of apps that you use (more if you use virtual machines), but at least you're protected.

We have released Fatdog64 721 with updated kernel (4.14.12) that comes with this workaround.

You can, however, decide risk it and not use the workaround, by putting "pti=off" boot parameter. You'd better know what you're doing if you do that, though.

Apart from that, this release also supports microcode update and hibernation. We've bundled the latest microcode from both Intel (dated 8 Jan 2018) and AMD (latest from linux-firmware as of 10 Jan 2018); however it is unclear whether any of them address the problem.

Release Notes

Announcement (same announcement as 720).

Get it from the usual locations:

Primary site - ibiblio.org (US)

nluug.nl - European mirror

aarnet.edu - Australian mirror

uoc.gr - European mirror

No comments - Edit - Delete

How to destroy FOSS from within - Part 4

This is the fourth installment of the article.In case you missed it, these are part one and part two and part three.

I originally planned to finish this series of articles at the end of last year, so we start 2018 with a more uplifting note - but didn't have enough time so there we are. Anyway, we already start 2018 with the biggest security compromise ever (that CPU-level memory protection can be broken even without any kernel bugs, that kernel memory of any OS in the last 20 years can be read by userspace programs) - one more bad news cannot make it worse.

And now, for the conclusion.

By now you should already see how easy it is to destroy FOSS if you have money to burn.

From Part 2, we've got conclusion that "a larger project has more chance of being co-opted by someone who can throw money to get people to contribute". This is the way to co-opt the project from the bottom-up - by paying people to actively contribute and slowly redirect the project to the direction of the sponsor.

From Part 3, we've got the conclusion that "direction of the project is set by the committers, who are often selected either at the behest of the sponsor, or by the virtue of being active contributors". This is the way to co-opt the project from top-down - you plant people who will slowly rise to the rank of the committers. Or you can just become a "premium contributor" by donating money and stuff and instantly get the right to appoint a committer; and when you have them in charge, simply reject contributions that are not part of your plan. Or, if you don't care about being subtle, simply "buy off" the current committers (= employ them).

In both cases, people can revolt by forking, if they don't have the numbers, the fork will be futile because:

a) it will be short-lived

b) it will be stagnant

and in either case, people will continue to use the original project.

It's probably not the scenario you'd like to hear, but that's how things unfold in reality.

In case you think that this is all bollocks, just look around you.

Look around the most important and influential projects.

Look at their most active contributors.

Ask yourself, why are they contributing, who employs them.

Then look at the direction these people have taken. Look very very closely.

Already, a certain influential SCM system used to manage a certain popular OS, is now more comfortable to run on a foreign OS than the OS that it was originally developed (and is used to manage).

Ask yourself how can this be. "Oh, it's because we have millions of downloads of for that foreign OS, so that foreign OS is now considered as a top-tier platform and we have to support that platform" (to the extent that we treat the original OS platform as 2nd tier and avoid using native features which cannot be used on that foreign OS, because, well, millions of downloads). Guess what? The person who says that, works for the company that makes that foreign OS. And not only that, he's got the influence, because, well, there are a lot of "contributors" coming from where he works.

What's next? bash cannot use "fork()" because a foreign OS does not support fork()?

Who pays for people who works on systemd? Who pays for people to work on GNOME? Who pays for people to work on KDE? Who pays for people who works on Debian? Who are the members of Linux Foundation? You think these people work out of the kindness of their heart for the betterment of humanity? Some of them certainly do. Some, however, work for the betterment of themselves - FOSS be damned.

No comments - Edit - Delete