CSVfix patches for regex and exec

CSVfix is a tool for manipulating CSV files. Along with the usual column re-ordering and filtering, CSVfix offers a powerful per-cell data transformation using a simple expression language, as well as regular-expression for string matching and editing. And if this is not enough, CSVfix can execute external process - for every cell that needs to be processed. And oh, it's available for Windows too!I find this tool to be very handy in what I need to do, so when I encountered a bug in its regex processing (for its "edit" command), I immediately checked if there is any updates to this tool. Unfortunately, its development seems to have ceased in 2015; and no other people seem to have picked up the development (I did find some forks, but they were all older copies from when it was still hosted in google code).

So I set out to figure out about the problem and hopefully rectify it. I found that the problem was in its regex library, which was a home-grown library (apparently adapted from an algorithm book). It is 2020 as of this time of writing, and C++ now comes with its own STL regex library (std::regex). I decided to rip off the custom regex lib and replace it with the STL regex instead, while keeping the rest of the class interface identical, therefore no other part of the code needed to be changed. This instantly fixed the problem, and as a bonus, now we can use ECMAScript-compatible regex instead of just the basic regex.

Later, I found out that the "exec" command also had a bug (the flag "-ix" did not work properly), so I traced this and fixed it too.

Oh, and during the process, I tried to run its testsuite - and while most of them passed, some did fail. Mainly because of CRLF/LF inconsistencies, so I changed those the test data to use LF. It is also a warning that this tool only works with platform "newline" - CRLF in Windows, and LF in Linux - so if files were to be exchanged between platforms, they must be properly translated first before use.

Here are the individual patches.

- regex patch

- exec patch

- test-case patch

They apply on top of the commit 93804d4 from 2015-02, which was the latest when I wrote this. They are licensed in the same way as the original CSVfix is licensed.

If CSVfix is not powerful enough for you, there are other similar tools:

1. miller is a tool in very similar spirit with CSVfix, but it is (much) more sophisticated. Its "data transformation language" looks more expressive than the one in CSVfix. If you have a problem you cannot solve with CSVfix, miller will probably help you. As a bonus, it is still in active development - that means bugs will be squashed. It is written in C, you will need to compile it if it is not in your package repository. (Fatdog, naturally, has it in its repository).

2. csvkit is a collection of tools that more or less perform the same functions as CSVfix. It supports direct conversion to/from Excel files, importing/exporting into databases (sqlite and postgresql as documented, perhaps others too), as well as running direct SQL queries from CSV files (and databases too). It is written in Python3 so you can install it using pip3. Fatdog has this in its repository too (so you can install it using package manager instead of pip3).

3. rbql basically enables you to run SQL-like on CSV files; but its power is its ability to run python (or javascript, depending on which backend you choose) code for every cell. Fatdog has it in its repository too, although you can just use pip to install it, if you don't run Fatdog.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Fatdog64 801 is Released

It is a rolled-up updates, containing bugfixes and minor feature updates.Release Notes and Forum announcements

Get it from the usual locations:

Primary site - ibiblio.org (US)

nluug.nl - European mirror

aarnet.edu - Australian mirror

uoc.gr - European mirror

ISO Builder: Get it from here: http://distro.ibiblio.org/fatdog/iso/builder/ and choose the builder dated 2019.05 and the package list for 801.

Enjoy.

Comments - Edit - Delete

The Road to Fatdog64 800 Alpha

Today, the first of Fatdog64 800 series is released to the wild - the Alpha release. Despite being labelled "alpha", this release has been tested for a few months and has been used day-to-day in real production machines (in varying degrees) for about two months by all of us, in the team.It has not been a smooth ride all along. Living in the "bleeding edge" means that you really need to prepare to bleed (that's why we don't update the base on every release - it would be downright impossible). Latest packages don't always build, and when they do, they don't always run, and they do, they don't always run stably, and when they do, they don't always work, and when they do, they don't always work correctly, and when they do, they don't always provide good performance, and so on, and so on - you get the picture.

But we have finally arrived. It may not be perfect, and it never will, but for us - it is good enough for day-to-day usage; so the decision to release.

This blog post documents a few of the stumbling blocks that we passed through on our way to the Alpha release. By sharing the knowledge, I hope that others on the same journey can avoid them.

Warning: the information that comes after this is going to be very technical. Don't worry if you don't understand it - just use whatever that you do.

The particular bug that took as considerable time (weeks) to solve was this: it's a bug that causes the desktop to unpredictable, involutary exit to the console.

And it turns out, this problem has __multiple__ underlying causes. Each cause ends up with the X server exiting (sometimes gracefully and sometimes not) so that we're dropped back the console.

Sometimes there crash messages in Xorg.0.log, sometimes don't. Sometimes the exit is immediate (X goes down and we're back in the console), sometimes it's gradual (applications start to fail one by one, before X itself finally gives up its ghost and dies).

Bug #1: fontconfig doesn't like its cache to be tampered with.

This bug happens only when running with the RAM layer (savefile=ram:device:xxx, in Puppy's parlance this is pupmode=13). When anything that uses fontconfig starts (e.g X, gtk2, etc), fontconfig will be initialised and its first action is to scan all the font directories and makes its cache.

When we run using the RAM layer, these caches are stored in the RAM layer, and eventually will be "merged-down" to the actual savelayer (copying the files from the RAM layer to the savelayer, and then removing the copy on the RAM layer, and then refreshing the aufs layered filesystem so that the copy on the RAM layer gets re-surfaced on the root of the filesystem).

This has worked for the longest time, but we found out that in Fatdog 800 this isn't the case. Even the process of copying the files from RAM layer to savelayer (not even deleting them) triggered a cascade of failure in fontconfig, which eventually resulted a crash in all higher-level libraries and applications that uses this.

Fixes #1: We still don't really know what changed - this could be a change in the kernel, fontconfig itself, glibc, or others (remember, in 800, with a new base, **all things were updated** so we can't easily isolate one component from another), but once we know what triggered the collapse, we worked around it by making sure that fontconfig caches are not touched during the merging process.

Bug #2: Xorg server crash on radeon-based systems when DRI3 and glamor is enabled (the default settings).

This has been a long running bug due to Mesa (open-source OpenGL 3D library) changing its infrastructure to support newer, more powerful radeon cards, changing both the acceleration API (DRI2 to DRI3), acceleration methods (EXA to glamor), memory management (GEM, GBM, etc).

But the bug isn't in Mesa alone. Eventually Mesa needs to interface with the video driver, so co-operation with xf86-video-ati driver is needed.

And then there is the kernel too, the radeon DRM driver from the kernel.

There are multiple components and every component is a potential source of failure (which in this case they all contributed to the problem one way or another).

To make it worse, the problem is completely unpredictable. The system can run hours without a glitch before the desktop crashed, or it can crash in next hour after booting. It brought a completely un-reliable experience.

There is no good solution for this because every component keeps changing, so updating one component could very well break another. All we can do is watch bugzillas, forums, mailing lists, and listen to possible solutions.

Fixes #2: I think in this case, we got lucky. Most of the bugs were fixed in mesa 18.2.3, and the final bug was fixed in xf86-video-ati git-master, one commit after 18.1.0. We're going to stick with this combination for a while!

Bug #3: After an unpredictable amount of time, Xorg server will crash (due to failed assert), giving up messages similar to this:

[xcb] Unknown sequence number while processing queue

[xcb] Most likely this is a multi-threaded client and XInitThreads has not been called

[xcb] Aborting, sorry about that.

pidgin: xcb_io.c:259: poll_for_event: Assertion `!xcb_xlib_threads_sequence_lost' failed.

There is one unanswered report here: https://bugzilla.redhat.com/show_bug.cgi?id=1582478

This initially happened on ROX-Filer when it was worked heavily, so naturally we thought the problem was with ROX-Filer. But then it started to happen elsewhere (other GTK applications), so it could be anywhere in gtk2, glib, glibc, aufs kernel module, or even the kernel itself.

We scoured for solutions for similar problems, and we got some solution like this: https://forum.freecadweb.org/viewtopic.php?t=28054

But they don't work and they don't make sense. FreeCAD is a 3D-heavy application, so disabling DRI3 and (in some others links, disabling 3D hardware-acceleration) doesn't make sense for applications like ROX-Filer which is purely 2D and doesn't make use of any acceleration at all.

This was especially difficult to pinpoint because it happened randomly; and it was one of the thing I would have filed into "unsolved" files, were it not for SFR. SFR found a way to reproduce this problem reliably (by clicking the "refresh" button on ROX-Filer a few hundred times - and he even provided a automation script so we don't have to buy a new mouse after every experiment

).

).

Once we can reproduce this, re-building the libraries with debug symbols and running them under "gdb" quickly pointed out that the problem is within libxcb - a library at the bottom of the Xorg stack.

Bisecting on libxcb, we found that the problem is caused by a particular code commit that tries to "fix" another bug when dealing with Vulkan drivers:

https://cgit.freedesktop.org/xcb/libxcb/commit/?id=fad81b63422105f9345215ab2716c4b804ec7986

But the way it was fix is, in my opinion, is incorrect (it was reading stuff when it shouldn't - this kind of thing should be protected with a mutex or we'll end up with a race).

Fixes #3: So we reverted this commit and poof! - the problem disappears. I tested clicking the button to about 16,000 times and no more crash.

This was the last bug we squashed.

So there. One symptom, three underlying problems, that can be triggered at different semi-random times, resulting in a totally different error messages and behaviour, confusing all of us.

We falsely declared victory after the first and the second were squashed - only to be humiliated when the crash happened again, in a slightly different way. By the time we squashed the last bug, we were wary enough __not__ to declare it fixed until a few days later and it was finally confirmed that we've finally made it through.

All in all, we spent more than a month to solve all of them. Now that we've past through them, I hope others can avoid the same mistake.

Meanwhile, enjoy Fatdog64 800 Alpha!

Forum announcement here: http://www.murga-linux.com/puppy/viewtopic.php?t=114719

Release Notes here: http://distro.ibiblio.org/fatdog/web/800a.html

Comments - Edit - Delete

So you want to roll your own distro?

This was supposed to be posted a week ago. So "today" in the text was actually about 10 days ago, give or take. Since then, all of us in the Fatdog team have migrated and are now eating our own dog food. But it doesn't change the essence of the post.Today has been an exciting day for Fatdog64. For me at least, Fatdog64 800 has now entered the "eat own dogfood" phase. I have migrated my build machine to Fatdog64 800. In another word, Fatdog64 800 is now self-hosting. This is the the phase that we have always done since the early days of Fatdog - we use it ourselves first, internally, for actual day-to-day purposes, to make sure we weed out the most obvious and most annoying bugs. We suffer these bugs so you don't have to. Of course, some would still slip out; and that's why more testers means lesser bugs; and fortunately, there are now four of us in the Fatdog team, and we have helps from other pre-release testers too. We'll stay in this phase for as long as it is needed to polish it up.

It has been a long and winding road to get to this. For those people who aren't involved, they probably aren't aware of the effort that goes to a project like this. Some people says, a distro is just a collection of stuff, right, and you don't write that stuff - you just package them. What's so hard about it? To that, I could have replied "well if you think it's so easy then why don't you do it yourself" - but instead, I'd choose to explain what happens behind the scenes. Along the way, I can explain some key decisions that makes Fatdog what it is today.

Let's start.

Okay, so a distro is just a collection of "packages". That's correct, in general, but as in everything, the devil is in the details. First and foremost: where do these "packages" come from? You've two choices here: build your own, or use someone else's. If you use someone else's packages, then your distro effectively is a "derivative", even if you call it that way or not.

We don't want Fatdog to become a derivative, at least, not Fatdog64 (I have another stagnant project called Fatdog-Like which *is* a Fatdog derived from a parent distro - but it's not going anywhere at the moment due to lack of time and interest), and the reason is not because we simply don't like to be called as "derivative".

The reason is deeper: it's about management and control. Using someone else's packages means you don't have full-control over the decisions that goes into the making of that packages - from the simple things like "which version is available", to more complex things like what is the optional libraries linked to it (this determines overall size and functionality); where is the configuration data stored; what is the build-time configuration parameters, etc.

Okay, so we don't want to be derivative.

We want to strike it on our own. What's next?

Well, what's next is we need to build our own packages then. Before we build our own packages, there are a few things that we need to sort out. Firstly, the compiler. A compiler is special, because, a part of the compiler is always attached to the final program (=the run-time). If you use an existing compiler, whoever made that compiler already made a decision for you (at the very least - the version of the compiler), which will get carried on to all of your packages --- even if all those other packages are built by you. So, no, we cannot use an existing compiler, can we? We have to build our own compiler ourselves (more popularly known as the "toolchain" because a compiler is just one of the components that you need to build a program from source - there are also the linker, the libc, and others. I'd gloss over the problems that a correct functioning toolchain requires very specific combination of correct versions of its components).

Well, how to build a compiler then? It just another package, right? No. The compiler we build is special - the program it will build is not meant to run in the machine that the compiler is run; instead, that program is supposed to run in our brand new distro, which currently exists in the gleam of our eyes only. Building a compiler like this is what you call as "toolchain bootstrapping" (aka chicken-and-egg problem); and the compiler you produce this way is a cross-compiler. I'm not going to explain terms like this here - I will assume that if you're interested enough to read this, you have enough motivation to google for terms that you don't understand.

Ok, you've googled it - and as it turns out there are tons of tools to build a cross-compiler! There is "buildroot" from busybox team, and there is "crosstool-ng", and there are many others! Problem solved, no? Eh, the answer is still no. Most of these tools produce a cross-compiler all right, and they do it very beautifully. Only one problem - most of these tools are NOT capable of building a cross-compiler which can build a native compiler (that is, a compiler that will eventually run in the target system). Which means that we will forever be dependent on them to build packages for us. That is not good. We need a cross-compiler that can eventually build a native compiler so that we can use native compiler to build the rest of the packages.

Actually, any good cross-compiler can be used to build a native compiler. You just need to know how. And it's not easy. Even the process of building a corss-compiler itself is almost black magic - that's the reason why there are numerous tools that help you to do it. Fortunately, there is one project that aims to decipher all these gobbledy-gook into something that you can understand. That project guides you, step by step, through the process of making a cross-compiler, and how to build a native compiler. That project is the Linux From Scratch project (LFS). It is not a tool, it will not build a compiler for you, but it is a book, a guide, that will instruct you exactly how to do it, step by step, while explaining why certain things must be done in a certain way.

Fatdog64, since version 700, is based on LFS.

Once we've got the compiler, then we need to build the packages using it. The LFS is extremely helpful, it will guide you to build minimal set of packages that will enable you to build a minimal system that can boot to a console, in a bash shell. And that's when LFS ends. You end up with about 50 packages gives or take including the toolchain. But at least your target distro is now alive, with a native compiler in it that you configure it yourself (the LFS instructions are just a "guide", and you're welcome to vary it for your own needs once you know exactly what you're doing - so what you build is effectively your own compiler, not LFS'), that you can use for building the rest of the packages.

Ok. The rest of the packages. Where would they come from? Let say, ummm, you want to build a web browser. Firefox sounds good. Okay. How do build a Firefox web browser from scratch? Go to Mozilla website, spend a couple of hours digging in and out ... oh, I need to build a "desktop" first before I can even begin to build Firefox. And even with the desktop, there are these "libraries" that I need to have in order to build it. I also need tools - and certain tools must be very specific version (e.g. autoconf must be version 2.13 exactly and nothing older or newer). But how to build a "desktop"? A desktop is system of many components - quickly broken down to window managers, panel manager, file manager, system settings ... and then the basic graphics subsystem, of which you can choose between X desktop and Wayland as of today. X is more popular, so you decide to explore it - then you have X libraries, XCB libraries, input drivers, video drivers, and servers. And all those things needs supporting libraries before you can even build them - they need gzip libraries, XML libraries, etc down the rabbit hole we go. So how do we even start?

Well, within the umbrella of the LFS project (but run by different people), there is this project called BLFS - Beyond LFS. Its purpose is, you guess, to provide details about building packages which aren't part of LFS. For every package that it describes, it tells you: (a) where to get the source files, (b) what are the dependencies for that package (=what packages must be built and installed before you can build this one), (c) the commands to build it properly. BLFS is much larger in scope than LFS but even it does not cover everything. It will get going, though, as it says at the top of the book: "This book follows on from the Linux From Scratch book. It introduces and guides the reader through additions to the system including networking, graphical interfaces, sound support, and printer and scanner support." So it does get you going in the right direction. It even tells you how to build Firefox, and what exactly you need to build before you can do it (you're still going down the rabbit hole, but at least somebody holding a ladder so you can always climb back up).

Fatdog64, since version 700, uses parts of BLFS as the source of some of its packages.

But there is on major problem here. Both LFS and BLFS shows and guides you to build an operating system for yourself. It's like building a one-person distro. You cannot easily copy the resulting system into a distribution media, not without tainting it with your own personal information and machine-specific configurations. (the keyword is here "easily" - with enough effort surely you can do it - obviously WE are doing it for Fatdog64). No matter, you say. I'm just building a distro for one, for myself. So all is good, right? No. With the LFS (and BLFS), it is easy to add new packages into the system, but it is rather difficult to get rid of an installed package. All packages are installed to the target system as they're built, without any records of which files goes where; so it's difficult or even impossible to remove without breaking the system.

The ability to track installed packages, and thus remove them (in addition to installing one) is collectively known as "package management". Any decent distro has one. Package Management is not included in LFS/BLFS because it "gets in the way" of explaining how things works - which its main objective. It only goes as far as saying that a package management IS needed, and there are many possible ways to do it. Look it at LFS Chapter 6.3 if you're interested.

So, you need a package management. A package management has two parts - the "creator" that enables you to build a "bundled" package, and the package management proper that can install/uninstall/view installation of your "bundled" packages. The "creator" part must be used in conjunction with your build process; because it needs to keep track of the files produced by your build, collect all those files, and bundle them up in package.

Easy, you say. Just google it up, and you will find "porg". Or you can even use existing package management system. After all, many distros share the same system; it is unnecessary to invent a new package management system (yes, proper and correct package management system is HARD). Why don't I just take Debian's package management system (dpkg), or RedHat's one (rpm), or Slackware's one (tarball), or many other myriads ways that have been suggested?

Well yes we can.

From version 700 onwards, Fatdog64 uses Slackware's package management system ("pkgtools"), fortified with slapt-get from jaos.org, modified for our use.

"pkgtools" is choosen because it's easy to create its packages, it's easy to host and publish the packages, it has tools that can extend it to support remote package management and dependency tracking (slapt-get), and the packages are basically tarballs that - in the worst case - you can always "untar" to install without needing special tools. No other package management tools comes even close.

Okay, once you choose a system then you need to hook it up with your build system so that the "creation" part of the package works, as I said above. I'd gloss over this fact and assume you can already do it. Let's move on.

Hang on, you said. We already bootstrap a system, have enough guides to build everything up to a web-browers and multimedia player (vlc), can install and uninstall packages, so what's next?

Ok, what's next? How about package updates. Software is being updated. What's new yesterday is old today and obsolete tomorrow. You need to keep building packages. These updates are not in the LFS/BLFS books, because they're published semi-annually. In between, if there is any updates, you must roll on your own sleeves and figure out how to do it yourself (it shouldn't be too hard now if you can follow BLFS guides this far). Ok, so updating is easy. *IF* you do this everyday. But if you don't - well, do you still remember how you built the previous version of the package? Do you remember the build-time flags you specified 3 months ago? Welcome to the club - you're not the only one.

You first response to the question is - I will make sure I keep a note of all the configurations, library dependencies, etc etc when I build the packages. Or, perhaps, even simpler, I will just stick to LFS/BLFS update cycles, so no need to write my own notes. I'm not that desperate to live in the bleeding edge anyway.

OK. If you decide to stick to BLFS, I have nothing else to say, but if you said you'd want to keep notes, then allow me to go a bit further. Rather than making a note, which you need to "translate" into your action when build the package, why don't you write them in the "scripting" language? So next time you can tell the computer to "read" your script for you and do the build too. Sound nice and too good to be true? It isn't, and it is actually the perfect solution. With a "build script", not only you know remember how to build a package, you also save time and (with exceptions) you have accomplished a "repeatable build" - which means that you can repeat the build many times and get a consistent result.

After a while, not only you want to record the build process, you may as well keep a record the location of the source package, perform the download, identify that the downloaded source package is correct (using checksum) before actually building it. You may even want to keep information about library dependencies there.

And if you're like me, after a while you will start to notice two things. (1) About half the content of the script is identical. It's always wget (or curl), then md5sum (or sha512sum), then extract, then apply patches, and build, then activate package-management-creator hooks, and then install and make package. The (2) point that you notice is that with the proliferation of build scripts, you need to manage them, and have the computer build them in the correct order (instead of you manually sorting out the build order).

Congratulations. You have recognised the need for a distro build infrastructure (shortened as "build system"). What we have been calling as "build scripts" are usually known as "build recipes"; once we take out the "scripting" out of them and move them into shared build infrastructure. Some people consider build infrastructure part of package management (because they can be very closely coupled) but they're actually separate systems.

Most major distros have their own distro build system, for example, Debian has "debuild", RedHat has "rpm", Arch Linux has "PKGBUILD", Slackware has SlackBuilds (for 3rd party packages only), etc. Each of these build systems have their own way to specify the "recipes" - some highly structured like debuild and rpm, some are rather loose like Arch PKGBUILD. You can use them, you don't have to re-invent the wheel. Of course, you can also come with your own if you wish.

Fatdog64 uses its own home-brewed build system conveniently named "Fatdog pkgbuild" (no relation to Arch Linux build system of the same name).

Simply because we found that none of the existing build systems have the features that we need (mainly simple enough to be understood and written but flexible enough to build complex packages). Fatdog64 build's system is more loosely defined (similar in spirit to Arch Linux) as opposed to the highly structured build system like rpm or debuild. It has proven itself enough to be able to build a customised firefox and libreoffice in a single-pass.

Ok. You have now gone a long way from building packages by hand manually and installing directly (./configure && make && make install). You are now the proud owner of a build system that can (re-)build the whole system in one command call. With some clever scripting you can even make install these packages into a chroot, and create an ISO file ready for distribution. Your job is done, you're now official an distro builder! Congratulations!

But wait. I don't have to go through all these processes. There are already "distro build system" out there, complete with fully populated recipes for every software under the sun and the moon! There is one called T2-SDE, for example. "buildroot" from busybox can actually build an entire distro's worth of packages by itself, all nicely packaged into tarballs too. Or you can start with debootstrap from Debian and start working your way up - Debian publishes every single one of their recipes, from every version ever released. And wait, they're not the only one. You have openwrt, you have ptx-dist, you have open-embedded, you have gentoo, you have yocto, and many others that I've forgotten. (You can even include android in the list - yes AOSP is a distro build system). Why not just use them?

Well, why not. If you like them, then by all means use them. Just remember this: every single build system released out there, is released to serve a purpose. Investigate that purpose is, and see if it is aligned with what you want to do. Also, all those build system (and recipes) are maintained by others, and they follow different objectives and schedules than you. This may or may not be important for you.

Fatdog64 500 and Fatdog64 600 were originally build using T2-SDE. T2-SDE was the build system used to build packages for earlier Puppy Linux builds too (version 4.x - the Dingo series). The reason why we drop T2-SDE is again because of management and control. Having T2-SDE is great because we don't have to bother about recipes and upgrades anymore, someone else is taking care of that for us. But it also means that version updates etc depends on the maintainer. Adding new packages (new recipes) depends on the maintainer. Etc. We can of course update the recipes on our own (once we understand the format), but then it means we to start keeping track of these recipes ourselves. The more we have to change, the more we have to maintain ourselves. Some packages' changes only affect themselves, some affect others (e.g. library updates more often than not introduces incompatibilities, which means that all packages that uses this updated library will now also have to be updated themselves, causing an avalanche of recipe updates), so before you know it, you basically have "forked" your build system from the original maintainer. This is even more true if you find "bugs" in the build system which the maintainer won't fix for whatever reasons, and you ends up fixing it yourself. Congratulations, you're now maintaining a distro build system that you don't fully understand and was created by someone else for objectives that may or may not align with yours.

So, okay, you decide to start a build system on your own. At least, this is your system, you know it upside down and you can debug it with your eyes closed. You write this exactly to your own needs - nothing less, nothing more. Then you start to populate this system with recipes.

You can initially source the recipes from BLFS, and then you can start writing your own, or even use recipes from Debian, RedHat, OpenSuse, Arch, or wherever else you can find them. Lots of time spent in experimenting to make sure that the right combination of packages and libraries all work well together and produce the best outcome that you want (in terms of feature, performance/speed and size). If you use only one source (e.g. BLFS) this is not important - the tuning is already done for you. But if you mix recipes from many sources, they have have assumptions that is no longer true when you apply them in your system (e.g. assuming a library is installed when it is not, etc); you will find out when you get a build failure (or worse: a run-time failure) so you have to tinker and adjust. Imagine, then: at the very near end of the building, you've got a compilation failure. You've got to troubleshoot this, figure out why it fails, what's the probably fix, and try to build again. And it fails again. So you investigate again, and try fixing up again. And then rebuild. This cycle continues until you finally get a working recipe that builds correctly, or until you give up. But if this is a very important library which is used by many other packages, "giving up" is not an option (unless you want to give up building the distro altogether). Now imagine this trial-and-error cycles, for a large package like libreoffice which can easily take a few hours to build. A single, big, and yet important recalcitrant package can easily delay progress by days.

Of course you're not always on your own. I don't want to make it sound more difficult than what it is. stackoverflow.com is here to help. You can also ask linuxquestions.org or similar places, and if you're lucky, you're not the first one to encounter the problem, so google is your friend. But once a while you do get unlucky and the problem you need to solve is truly yours only.

Anyway, let's move on. After spending countless, sleepless and thankless hours building your distro, finally come to the period of testing (which is where we are at, now, for Fatdog64 800). This is where the proof meets the pudding - see if those recipes get us a good cake. And then only way to know whether the food is good is to eat it, so the mantra "eat your own dog food". After an eternity of testing, you finally come to the conclusion that you're going to have to publish this distro or it will be obsolete before it is released.

Congratulations! It's release time! (We're not there yet for Fatdog64 800 - but we have been through this many times with earlier versions - you can refer to all our previous releases in Fatdog History site). To be on the safe side, you don't immediately claim for the Final release (aka "Gold" release), but you call is a "test" release and call it using Greek alphabet to make it cooler (alpha release, beta release etc - but normally it stops at beta because "gamma" sounds very bad for your health - after all gamma radiation is what turns Bruce Banner into Hulk, remember?).

And then the silence is deafening. Nobody (in their right mind) will touch a test release within a 10-feet pole (unless they're dedicated testers, and thankfully, over the years we have managed to attract some of them - so the silence is not usually deafening for Fatdog release. But others don't fare as well). Oh well, after a few weeks of test release, we think we've squashed all the bugs we can find (and willing to, and able to fix). It is now finally the time for the Grand release, aka Final, the Gold.

Drum rolls please!

As soon as we made the final announcement, comes the news that the kernel we included in the final release has a severe CVE problem (privilege escalation). Or that the openssl version that we use has CVE reports about remote exploits. Or the install scripts corrupts the user's hard disk. Or there is yet one more bug that we missed earlier in the test release. This is not including people whose only sorry life's existence depends on trolling people (Again: this paragraph, like the the rest of this post, is illustration only. We don't usually get it so bad - in fact we've evaded the worst and fared quite well in our releases so far). So what can you do? Depending on the severity of the problem, you can: (a) ignore it, or (b) fix it and issue a minor version update, or (c) pull out the release completely until you can work the problem out. Oh, and just ignore the trolls.

But the life of a distro doesn't end here, unless you're fine doing just doing one-trick pony. Software gets updated, bugs got found, more CVEs got reported, so you've got to update your releases too. Sounds familiar isn't it. But you've got your build system! You've got your recipes! So no problem, right?

You update your recipes, (re-)build them in your build system, spending more countless hours fixing breakage caused by the updated recipes, etc. And then you issue an update - this can be package update, or build a new ISO and issue a minor revision release, etc. Generally it's quite manageable unless you're trying to "live in the edge" and wants to always be on the latest version on everything (note of warning: bleeding edge is not wise. Newer versions comes with fixes but also comes with new bugs too).

But updates doesn't last forever. There are components of the system that you can't update. "libc" for example. It is part of the toolchain. It is part of every software in your distro. To update it, firstly you need build a new toolchain. Secondly it means either (1) you need to rebuild all the packages with the new toolchain - this is the proper way of doing it, or (2) just drop the old libc and put in a new one - this is the improper way of doing it and has great risks of introducing unpredictable crashes. In other words, unreliablity.

So, eventually, you have to do the proper way (1) above. This is what in Fatdog64 parlance is what we call as "updating the base". It is what comprises a major release, in Fatdogs. All minor version updates have the same base - same compiler, same libc. For example 600, 601, 602, 610, 611, 620, 621, 630, 631 releases all use the same toolchain and same toolchain libraries. When we move to 700 series, we have a new toolchain - "the base". Fatdog64 800 is one such major release - we're moving from gcc 4.8.3 and glibc 2.19 in 710 series to gcc 7.3.0 and glibc 2.27 in Fatdog64 800.

Naturally, when we have to rebuild all of the packages, we may as well update them as we go. So, not only we're updating the toolchain, but we're updating every single one of the packages that we have build previously. The fact that we've sourced some of our packages from LFS and BLFS doesn't help - we still have to review and update (all of) our recipes; and we still have to build it. Again, we while we borrow and use recipes from many sources (including writing our own as needed), the environment and the combination of packages that we build and use is completely unique to us, so basically we have to repeat the countless, sleepless, and thankless hours of tuning the updated recipes (=all of them) again and again, waiting for a package to build just to see the compiler spits out cryptic error messages because (a) new gcc now uses new c++ standards which considers previously accepted language construct as an error unless you know certain magic incantations that will bring its understanding of "ancient wisdom" back - but sometimes even such incantation doesn't work as advertised and you need to patch it (b) openssl has a new ABI that makes all other openssl-using packages to fail and must be patched (c) poppler changes some of the method signature for no good reason and causes undecipherable error messages to some, but not all, packages that uses it, (=me spending hours convincing scribus to build) or (d) Qt goes yet again for another re-factoring spree that breaks all except the latest of the software; whose fix is easy just insert #include <QStyle> but of course you must know that this is the solution (and on which file you need to insert it) (e) original website goes dead, need to confirm if this is the latest/final version of the software or if anyone picks up the debris and start a fork (f) change of source code hosting - we have been in the business long enough to see migrations sourceforge to googlecode to github and now to gitlab with pieces left along the way - so we need to confirm which hosting contains the latest (g) and many other fine gotchas in similar vein.

So. Having a build system makes maintenance oh so much easier. But when it comes to major updates like this, there is always serious work involved behind it. It is almost like re-starting everything from scratch again (because it actually is). Fatdog64 is relatively small, we have only about 1500 packages (not including the contributed packages), but even this takes considerable amount of time to maintain and especially to perform major update. To give you an idea, Fatdog64 800 work was seriously started not long after LFS 8.2 is released, in March (our based is based on LFS 8.2 - we started ours major cycle update around late May). At the time of this writing, LFS 8.3 has been been released, and we're still in internal testing phase.

Oh, one more thing. Even though we use LFS as the base, it is not purely LFS. LFS is not multi-lib aware. As early as Fatdog64 700 (which uses LFS 7.5), we've tried to build it in away that is 64-bit clean - that is, all 64-bit libs goes for "lib64". This we can tack on 32-bit compatibily libraries in "lib", using libraries we took from other 32-bit distros (mainly from Puppy Linux variants). In Fatdog64 710 we upped the ante and build a full multilib version - which means that both the build system now builds both 64-bit and 32-bit packages directly. One of the key parameter of success is the ability to build wine - which requires both 64-bit and 32-bit infrastucture to work. LFS is not multilib aware, does not support multilib, and does not plan to do it, because, doing so, will just obscure the points (same reason why package management is not included). And I fully agree.

To that end, in 710 our base was actually shifted to CLFS 3.0.0. CLFS - Cross-LFS is an extension of CLFS that builds Linux distros for target platform which is not identical to the original host platform (LFS requires that host and target platform to be the same - if you start on 32-bit system, you end up with 32-bit distro), and in addition, it supports multilib too. But in term of the age of the packages, CLFS 3.0.0 was very close to LFS 7.5 so that they're virtually identical (same glibc versions, gcc only differs in revision numbers, etc) so aside from the build infrastructure changes, CLFS-based Fatdog64 710 is identical to LFS-based Fatdog64 700.

The point is, we don't just take and use LFS/BLFS recipes (or any other 3rd party recipes) verbatim. We need to convert them into multilib-compatible recipes, we need to create the 32-bit version of the recipes, and lastly we need to test them that they build, and that they work. There is serious amount of work going behind the scenes that people rarely see.

And lastly - all those packages you build, you need to publish it somewhere, right? Debian users uses apt-get to install new packages. RedHat/Centos uses "yum". Arch uses pacman. What will your distro use? Where will you publish the packages? How to maintain and ensure that this "software repository" / "package repository" ("repo" for short) of yours is up-to-date? If you have a non-traditional delivery system like Fatdog64, whose entire operating system files are kept in the "initrd", how can you deliver updates? These are important non-rhetorical questions which I leave as an exercise for the reader.

So, do you still want to start and maintain your own "personal" distro?

Sure, writing and programming a software as complex as libreoffice is difficult and hard, especially always playing catch up to moving goalpost of "MS compatibility". Sure, writing and programming a web browser as complex as Chromium is hard - especially playing catch up to the "Living Standard". But building and maintaining a distro with over 1000 independent moving components created by different groups of people who may or may not be aware of each other is not exactly a walk in the park either.

It's fun, though. If you just have the right mindset. Which is why I'm still here, and will still be here for foreseeable future, ceteris paribus.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Fatdog64 800 development update

We have finally completed the base of the next generation Fatdog64 800. We have it running with 4.18.5 kernel (this will probably change nearer to release).We are still in the process of fine-tuning it, and trimming the size down. Size growth is unavoidable because newer version of the software are almost always bigger due to feature creep.

Apart from fine-tuning it, we're going to do the usual "eat own dog food" which is to run it ourselves for day-to-day use; this way we can iron out the most obvious bugs.

Once this get stable enough, it will then be ready for alpha release.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Some random updates

OK, let's start with Barry K, the original author of Puppy Linux and the spiritual grandfather of every "dog"-themed Linuxes out there, Fatdog included

For you who haven't read Barry K's blog recently, you should check it out. Barry has come out with new interesting stuff that should spice out your "Puppy" experience (strictly speaking, it's not Puppy Linux anymore - Barry handed over the baton long time ago. Instead Barry now does Quirky/EasyOS/etc - but as far as we're concerned, it's a "puppy" with a quote

).

).

Barry is also branching to 64-bit ARM (aarch64). I'm sure he will soon release an 64-bit ARM EasyOS. If you remember, Barry was also one of the first to venture to 32-bit ARM a while ago (a tad over 6 years ago) and made a Puppy that ran on the original Raspi. Quite an achievement considering that the original Raspi was barely able to run any desktop at all - but that is Puppy at its best, showing the world that even the weakest computer in the world can still run a desktop (as long as it's Puppy

). It was also one of the motivation that made me do FatdogArm.

). It was also one of the motivation that made me do FatdogArm.

Speaking about Raspi and FatdogArm, I have also recently pulled out my Raspi 3 out of retirement. But this time I'm not doing it for desktop replacement, but mainly because I'm interested to use it for what it was originally made: interfacing with stuff. Direct GPIO access, I2C and SPI is so interesting with the myriad of sensor packages out there. I've been playing with Arduino for a while and while it's cool, it's even cooler to do it using a more powerful platform. Now this article shows you how to do it directly from the comfort of your own PC (yes, your own desktop or laptop), if you're willing to shell out a couple of $$ to get that adapter. I did, and it is quite fun. Basically it brings back the memory of trying to interface stuff using the PC's parallel port (and that adapter indeed emulates a parallel port ... nice to see things haven't changed much in 30 years). But it's speed is limited to the emulation that it has to go through - the GPIO/I2C/SPI has to be emulated by the kernel driver, which is passed through USB bus, which then emulated by the CH341 on the module. If you want real speed, then you want real device connected to your system bus - and this is where Raspi shines. I haven't done much with it, but it's refreshing to pull out the old FatdogArm, download wiringPi and presto one compilation later you've got that LED to blink. Or just access /sys/class/gpio for that purpose.

Now on to Fatdog64 800. I'm sure you're dying to hear about this too

OK. As far as Fatdog64 800 is concerned - we've done close to 1,100 packages. We're about 200 packages away from the finish line. As usual, the last mile in the marathon is the hardest. It's bootloaders, Qt libs and apps, and libreoffice. Here's crossing your finger to smooth upgrading of all these packages.

OK. As far as Fatdog64 800 is concerned - we've done close to 1,100 packages. We're about 200 packages away from the finish line. As usual, the last mile in the marathon is the hardest. It's bootloaders, Qt libs and apps, and libreoffice. Here's crossing your finger to smooth upgrading of all these packages.

Speaking about updates, I've also decided to go for the newest bluetooth stack (bluez). I have been a hold-on on bluez 4 for the longest time, simply because the bluez 5 does not work with ALSA - you need to use PulseAudio for sound. But all of that have changed, ther e is now an app called bluez-alsa that does exactly that. I've been thinking to do it myself were it not there; but I've been thinking too long

Anyway, I'm glad that it's there. Bluez 5 does have a nicer API the last time I looked at it (as in, more consistent) though not necessarily clearer or easier to use than Bluez 4. But that's just Bluez.

Anyway, I'm glad that it's there. Bluez 5 does have a nicer API the last time I looked at it (as in, more consistent) though not necessarily clearer or easier to use than Bluez 4. But that's just Bluez.

Well that's it folks for now. And in case I don't see you... good afternoon, good evening, and good night

Comments - Edit - Delete

New Fatdog64 is in the works

It's the time of the year again. The time the bears wake up from hibernation. After being quiet for a few months, the gears start moving in the Fatdog64 development.Fatdog64 721 was released over 4 months ago. It was based on LFS 7.5, which was cutting edge back in 2014 (although some of the packages have younger ages as they got updated in every release).

As I have indicated earlier (in 720 beta release, here), 700 series is showing its age. Compared to previous series, the 700 series is actually the longest-running Fatdog series so far, bar none.

But everything that has a beginning also has an end. It's time to say goodbye to 700 series and launch a new series.

The new series will be based on LFS 8.2 (the most recent as of today). This gives us glibc 2.27 and gcc 7.3.0. Some packages are picked up from SVN version of BLFS, which is newer.

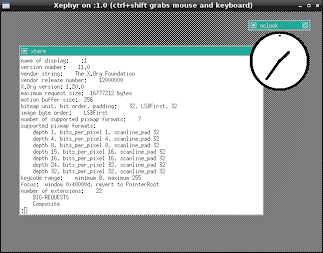

How far have we gotten with this new release? Well, as of yesterday, we've got Xorg 1.20.0 running with twm, xterm and oclock app running from its build sandbox.

Hardly inspiring yet, but if you know the challenge we faced to get there, it's a great milestone.

As it is usual with Fatdog64, however, it will be released when it is ready. So don't hold your breath yet. If 721 is working well for you, hang on to it (I do!). But at least you know that wouldn't be the last time you heard of this dog.

On a special note, I'd like to say special thanks to "step" and "Jake", the newest members of Fatdog64 team (and thus is still full of energy - unlike us the old timers hehe). While I have been shamelessly away from the forum for many reasons, "step" and "SFR" continue to support Fatdog64 users in the forum. My heartful thanks to both of them.

Of course, also thanks to the wonderful Fatdog64 users who continue to support each other.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Spectre on Javascript?

The chaos caused by Spectre and Meltdown seems to have quieten down. Not because the danger period is over, but well, there are other news to report. As far as I know the long tail of the fix is still on-going, and nothing short of hardware revision can really fix them without the obligatory reduction in performance.Anyway.

One of the those who quickly released a fix, was web browser vendors. And the fix was to "reduce granularity of performance timers" (in Javascript), because with high-precision timers, it is possible to do Spectre-like timing attack.

This, I don't understand. How could one perform Spectre or even Spectre-like timing attack using Javascript? Doesn't a Javascript program run in a VM? How would it be able to access its host memory by linear address, let alone by physical address? I have checked wasm too - while it does have pointers, a wasm program is basically an isolated program that lives in its own virtual memory space, no?

In other words - the fix is probably harmless, but could one actually perform Spectre or Spectre-like attack using browser-based Javascript in the first place?

That is still a great mystery to me. May be one day I will be enlightened.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Spectre and Meltdown

Forget about the old blog posts for now.Today the hot item is Spectre and Meltdown. It's a class of vulnerabilities caused by CPU bugs that allows an adversary to steal sensitive data, even without any software bugs. Nice.

Everyone and his dog is talking about it, offering their opinions and such. Thusly, I feel compelled to offer my own.

Mind you, I'm not a CPU engineer, so don't take this as infallible. In fact, I may be totally wrong about it. So treat it like how you treat any other opinions - verify and cross-check with other sources. That being said, I've done some research about it myself, so I expect that I'm not too much fooled by myself :)

Overview

There are 3 kinds of vulnerabilities: Spectre 1, Spectre 2, and Meltdown.

In very simplified terms, this is how they work:

1. Spectre 1 - using speculative execution, leak sensitive data via cache timing.

2. Spectre 2 - by poisoning branch prediction cache, makes #1 more likely to happen.

3. Meltdown - Application of Spectre 1: read kernel-mode memory from non-privileged programs.

How they work

So how exactly do they work? https://googleprojectzero.blogspot.com.au/2018/01/reading-privileged-memory-with-side.html gives you the super details of how they work, but in the nutshell, here it is:

Spectre 1 - Speculative execution is a phantom CPU operation that supposedly does not leave any trace. And if you view it from CPU point of view, it really doesn't leave any trace.

Unfortunately, that's not the case when you view it from outside the CPU. From outside, a speculative execution looks just like normal execution - peripherals can't differentiate between them; and any side effects will stay. This is well known, and CPU designers are very careful not to perform speculative executions when dealing with external world.

However, there is one peripheral that sits between CPU and external world - the RAM cache. There are multiple levels of RAM cache (L1, L2, L3), some these belongs to the CPU (as in, located in the same physical chip), some are external to the CPU. In most designs, however, the physical location doesn't matter: wherever they are, these caches aren't usually aware of differences between speculative and normal execution. And this is where the trouble is: because the RAM cache is unable to differentiate between these two, any execution (normal or speculative) will leave an imprint in the RAM cache - certain data may be loaded or removed from the cache.

Although one cannot read the contents of RAM cache directly (that would be too easy!), one can still infer information by checking whether certain set of data in inside the RAM cache or not - by timing them (if it's in the cache, data is returned fast, otherwise it's slow).

And that's how Spectre 1 works - by doing tricks to control speculative execution, one can perform an operation which normally isn't allowed to leave RAM cache imprint, which can then be checked to gain some information.

Spectre 2 - Just like memory cache and speculative execution, branch prediction is a performance-improvement technique used by CPU designers. Most branches will trigger speculative execution; branch prediction (when the prediction is correct) makes that speculation run as short as possible.

In addition, certain memory-based branch ("indirect branch") uses small, in-CPU cache to hold the location of the previous few jumps; these are the locations from which speculative execution will be started.

Now, if you can fill this branch prediction cache with bad values (="poisoning" them), you can make CPU to perform speculative execution at the wrong location. Also, by making the branch prediction errs most of the time, you make that speculative execution longer-lived than that it should be. Together, they make it more easier to launch Spectre 1 attack.

Meltdown - is an application of Spectre 1 to attempt to read data from privileged and protected kernel memory, by non-privileged program. Normally this kind of operation will not even be attempted by the CPU, but when running speculative execution, some CPU "forget" to check for privilege separation and just blindly do it what it is asked to do.

Impact

Anything that allows non-privileged programs to read and leak infomation from protected memory is bad.

Mitigation Ideas

Addressing these vulnerabilities - especially Spectre - is hard because the cause of the problem is not a single architecture or CPU bugs or anyhing like it - it is tied to the concept itself.

Speculative execution, memory cache, and branch prediction are all related. They are time-proven performance-enhancing techniques that have been employed for decades (in consumer microprocessor world, Intel was first with their Pentium CPU back in 1993 - that's 25 years ago as of this time of writing.

Spectre 1 can be stopped entirely, if speculative execution does not impact the cache (or if the actions to the cache can be un-done once speculative execution is completed). But that is a very expensive operation in terms of performance. By doing that, you more or less lose the speed gain you get from speculative execution - which means, may as well don't bother to do speculative execution in the first place.

Spectre 2 can be stopped entirely if you can enlarge the branch prediction cache so poisoning won't work. But there is a physical limit on how large the branch cache can be, before it slows down and lose its purpose as a cache.

Alternatively, it can be stopped again in its entirety, if you disable speculative execution during branching. But that's what a branch prediction is for, so if you do that, may as well drop the branch prediction too.

Meltdown however, is easier to work out. We just need to ensure that speculative execution honours the memory protection too, just like normal execution. Alternatively, we make the kernel memory totally inaccessible from non-privileged programs (not by access control, but by mapping it out altogether).

Mitigation In Practice

Spectre 1 - There is no fix available, yet (no wonder, this is the most difficult one).

There are clues that some special memory barrier instructions (i.e. LFENCE) can be modified (perhaps by microcode update?) to stop speculative execution or at least remove the RAM cache imprint by undo-ing cache loading during speculative execution, on-demand (that is, when that LFENCE instruction is executed).

However, even when it is implemented (it isn't yet at the moment), this is a piecemail fix at best. It requires patches to be applied to compilers, or more importantly any programs capable of generating code or running interpreted code from untrusted source. It does not stop the attack fully, but only makes it more difficult to carry it out.

Spectre 2 - Things is a bit rosier in this department. The fix is basically to disable speculative execution during branching. This can be done in two ways. In software, it can be used by using a technique called "retpoline" (you can google that) - which basically let speculative execution chases its own tails (=thus effectively disabling it). In hardware, this can be done by the CPU exposing controls (via microcode update) to temporarily disable speculative execution during branching; and then the software making use of that control.

Retpoline is available today. The microcode update is presumably available today for certain CPUs, and the Linux kernel patches that make use of that branch controls are also available today. However, none of them have been merged into mainline yet. (Certain vendor-specific kernel builds already have these fixes, though).

Remember, the point of Spectre 2 is to make it easier to carry out Spectre 1, so by fixing Spectre 2 it makes Spectre 1 less likely to happen to the point of making it irrelevant (hopefully).

Meltdown - This is where the good news finally is. The fix can be done, again, via CPU microcode update, or by software. Because it may take a while for that microcode update to happen (or not all), the kernel developers have come up with a software fix called KPTI - Kernel Page Table Isolation. With this fix, kernel memory is completely hidden from non-privileged programs (that's what "isolation" stands for). This works, but with a very high-cost in performance: it is reported to be 5% at minimum, and may go to 30% or more.

Affected CPUs

Everyone has a different view on this, but here is my take about it.

Spectre 1 - All out-of-order superscalar CPUs (no matter what architecture or vendor or make) from Pentium Pro era (ca 1995) onwards are susceptible.

Spectre 2 - All CPU with branch prediction that use cache (aka "dynamic branch prediction") are affected. The exact techniques to carry out Spectre 2 attack may be different from one architecture to another, but the attack concept is applicable to all CPUs of this class.

Meltdown - certain CPU get it right and honour memory protection even during specutlative execution. These CPUs don't need the above KPTI patches and they are not affected by Meltdown. Some says that CPUs from AMD are not affected by this; but with so many models involved it's difficult to be sure.

So that's it. It does not sound very uplifting, but at least you get a picture of what you're going to have for the rest of 2018. And the year has just started ...

EDIT: If you don't understand some of the terms used in this article, you may want to check this excellent article by Eben Upton.

Comments - Edit - Delete

Fatdog64 721 is Released

In the light of recent Spectre and Meltdown fiasco; the Linux kernel team has released patches to sort of workaround the problem.It's not free, you will get a performance hits anywhere from 5% to 30% depending on the kind of apps that you use (more if you use virtual machines), but at least you're protected.

We have released Fatdog64 721 with updated kernel (4.14.12) that comes with this workaround.

You can, however, decide risk it and not use the workaround, by putting "pti=off" boot parameter. You'd better know what you're doing if you do that, though.

Apart from that, this release also supports microcode update and hibernation. We've bundled the latest microcode from both Intel (dated 8 Jan 2018) and AMD (latest from linux-firmware as of 10 Jan 2018); however it is unclear whether any of them address the problem.

Release Notes

Announcement (same announcement as 720).

Get it from the usual locations:

Primary site - ibiblio.org (US)

nluug.nl - European mirror

aarnet.edu - Australian mirror

uoc.gr - European mirror

Comments - Edit - Delete